Those of you who are reading this blog should know that it is arranged in an order, not chronological, but of a journey around the province following Alexander Caulfield Anderson's footsteps. For this to make the most sense, it might be read from the earliest posting to the latest. I think that when it comes time for the book to be published, a new blog will be created that will follow the chapters of the book.

Following is an index, of sorts, of articles written before September 1st, 2009:

Anderson-Seton family:

July 16, 2009, The Anderson-Seton family tree

July 16, 2009, the Anderson-Seton family

July 22, 2009, General Sir James Outram

July 18, 2009, Elton Alexander Anderson, 1907-1975

July 26, 2009, James Anderson A, HBC

August 9, 2009, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Seton

Anderson and Seton Lakes -- August 23, 2009

Anderson's River Trail

August 2, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia

Brigade Trails

August 2, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia (Anderson's River trail)

August 23, 2009, New Brigade Trail, Copper Creek to Loon Lake

Earlier Index of Articles

August 1, 2009, Welcome to Alexander Caulfield Anderson's world

Fraser River

July 26, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia

August 2, 2009, Native Bridges in the Fraser Canyon

August 9, 2009, Salish Wool Dogs

General Fur trade

June 13, 2009, Anderson's Tree

June 19, 2009, Trade Blotter

June 21, 2009, The early fur traders' Carp

August 29, 2009, A short chronology of the fur trade in the New Caledonia district.

Kamloops

August 30, 2009, Sam Black

August 16, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia

Maps

August 23, 2009, Fort Langley via Kamloops to Fort Alexandria

Native Bridges in the Fraser Canyon

August 2, 2009

New Caledonia

August 29, 2009, A short chronology of the fur trade in the New Caledonia district.

Nicola Valley

August 16, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia

Rhododendron Flats -- July 25, 2009

Salish Wool Dogs -- August 9, 2009

Sam Black -- August 30, 2009

Thompson's River

August 9, 2009, Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia

1846, First Exploration

August 23, 2009, Anderson and Seton Lakes

1846, Second Exploration

July 25, 2009, Rhododendron Flats

June 13, 2009, Nicolum River

June 13, 2009, Anderson's Tree

1847 Exploration

July 26, 2009, Fraser River

August 2, 2009, Native Bridges in the Fraser Canyon

August 9, 2009, Salish Wool Dogs

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Sam Black

One of the most fascinating characters in Alexander Caulfield Anderson's fur trade was a man named Sam Black. Anderson met Black when he travelled with the 1835 brigade into New Caledonia with Black's good friend, Peter Skene Ogden. At the time that Black departed from Fort Vancouver with the outgoing brigade, he was Chief Factor in charge of the Thompson's River post (Kamloops).

Black was born in Scotland in 1780, and his uncle was the James Leith who was probably responsible for getting young Alexander Caulfield Anderson into the fur trade. Sam Black joined the North West Company in 1802, and during his early years in the Company's service, gained a reputation as a bully who used his large size and intimidating manner to frighten the men of the competing Hudson's Bay Company.

A few years later the North West Company sent him north to Fort Chipewyan District where he so harrassed Peter Fidler that the Hudson's Bay man removed himself from Nottingham House. Later still, Black spent 15 years in the Athabasca District where he took part in an argument in which 4 Hudson's Bay men were killed.

In the continuing battles between the Hudson's Bay men and the North Westers, Black became more hated than any other North Wester by the men of the Hudson's Bay Company. But in 1820, Black came face to face with George Simpson, who was in charge of a Hudson's Bay post in the Athabasca Country. Black found Simpson a difficult foe.

Simpson went on to become the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the North West Company began to lose the competition. By the time the Companies merged, Sam Black and Peter Skene Ogden had escaped to the territory west of the Rocky Mountains to avoid arrest. Both had been involved in the most scandalous battles between the two companies and, when the companies merged, both were left jobless. Black's letter shows his bitter disappointment:

"The communication received by one from the agents of the late N.W.Co. dated at Fort William, 17th July 1821, upon the subject of the arrangement with the Hudson's Bay Co. you will readily believe was most distressing to my feelings -- That a termination of the various oppositions betweeen the Companies was greatly to be wished for, and sooner or later to be expected, is certainly true; but I never conceived it possible that some of those whose zeal and exertion during the 'conter' brought about probably the necessity of negotiation on the part of our opponents, would be excluded from the benefits hoped for from that termination...." (North West Company correspondence 1800-1827, F.3/2, HBCA).

Ogden and Black fought for their jobs and within a year or two were granted positions in the Hudson's Bay Company. However, Sam Black was sent to take charge of Fort St. John (near Fort St. John, B.C.) and made a difficult exploration of the Finlay River where it ran through the Rocky Mountains -- a wild and absolutely unexplored area at that time -- while Ogden spent years exploring the Snake River District.

Finally after George Simpson believed that Black had been punished enough, he placed him in charge of Fort Colvile on the Columbia River, and later sent him to Fort Nez Perce (Walla Walla, Washington). However, Black was unable to get along with the natives and was transferred to Thompson's River post in 1830, where he spent many years.

Governor Simpson described Black's nature in his "Character Book" of 1832: "....the strangest man I ever knew. So wary & suspicious that it is scarcely possible to get a direct answer from him on any point, and when he does speak or write ... so prolix that it is quite fatiguing to attempt following him. A perfectly honest man and his generosity might be considered indicative of a warmth of heart if he was not known to be a cold blooded fellow who could be guilty of any Cruelty and would be a perfect Tyrant if he had any power....Yet his word when he can be brought to the point may be depended on. A Don Quixote in appearance, Ghastly, raw-boned and lantern-jawed, yet strong, vigorous and active. Has not the talent of conciliating Indians by whom he is disliked, but who are ever in dread of him, and well they may be so, as he is ... so suspicious that offensive and defensive preparation seem to be the study of his Life having Dirks, Knives and Loaded pistols concealed about his Person and in all directions about his Establishment even under his Table cloth at meals and in his Bed."

In 1841, Sam Black died at the hands of a native person at his Thompson's Lake post. In the late autumn of 1840, Black traded for goods with a local native chief, Tranquille, a man who was given this name by the voyageurs for his quiet good nature and calm. Tranquille arrived at the fort to pick up a gun that he had left behind, but Black refused to release the gun and reprimanded Tranquille. Tranquille returned home, chagrined, but relations between the natives and the Hudson's Bay fort remained in good standing.

But over the winter, Tranquille sickened and died. During the funeral speeches, a woman accused Tranquille's nephew of cowardice and urged him to revenge his uncle. The young man blackened his face and travelled to the Thompson's River fort on a freezing cold day, to sit in front of the fire. Black gave him a pipe, food and tobacco and left him alone. But in the late afternoon, as Black was putting his hand on the door of his quarters, the native shot him in the back, killing him immediately.

The native man made his escape, and John Tod came from Fort Alexandria to take over the fort and deal with the murderer. Fort Vancouver men also came north to hunt for the murderer who had abandoned his village and was hidden in the hills near Cache Creek. The Company men closed the fort to the local natives, causing anxiety and suffering among the people now almost entirely dependent on the fort for their supplies.

After a few days search the Hudson's Bay men found the murderer, and with the help of Chief Nicola's tribesmen, captured him. They tied the murderer's hands together and began their journey back to the Thompson's River fort. At the bottom end of Kamloops Lake the murderer upset the canoe they were travelling in, and floated down the river singing his war song. Nicola, who stood with a group of tribesmen on the south bank of the river, ordered his men to kill the murderer, and the boy disappeared under the waters of the Thompson River.

Peter Skene Ogden wrote about his good friend, Black, in Traits of American-Indian Life (London, 1853, reprinted recently in Oregon): "B... was one of my oldest and worthiest friends. Our intimacy had commenced some twenty five years ago, and been ripened by time into the warmest friendship. We had shared in each other's perils; and the narrow escapes we had so frequently experienced, tended to draw still more closely the bond of amity by which we were united. It was our custom to contrive an annual meeting, in order that we might pass a few weeks in each other's company. This renunion naturally possessed charms for both of us; for it was a source of mixed joy, to fight like old soldiers "our battles o'er again," over a choice bottle of Port or Madeira; to lay our plans for the future, and, like veritable gossips, to propose fifty projects, not one of which there was any intention on either part to realize."

Alexander Caulfield Anderson wrote of Sam Black: "Without having had the advantage of a critically correct education he was a man of great mental as well as literary attainments, and to the geology of the country he paid special attention. The geography too of the then only partially explored regions received through him many important additions. Of enormous stature and with a slow and imposing style of address Mr. Black, though he afforded possibly at times some amusement to his colleagues, commanded also their universal respect by his well recognized good qualities." (History of the Northwest Coast, by A.C. Anderson)

When Anderson died in 1884, he had a copy of Sam Black's 1835 map in his possession. This map has many details not shown on any other map of the area, but is very hard to read. It is now stored in the B.C. Archives, map no. CM/B2079, and R.C. (Bob) Harris writes about this map in B.C. Studies, No. 109, Spring 1996.

Black was born in Scotland in 1780, and his uncle was the James Leith who was probably responsible for getting young Alexander Caulfield Anderson into the fur trade. Sam Black joined the North West Company in 1802, and during his early years in the Company's service, gained a reputation as a bully who used his large size and intimidating manner to frighten the men of the competing Hudson's Bay Company.

A few years later the North West Company sent him north to Fort Chipewyan District where he so harrassed Peter Fidler that the Hudson's Bay man removed himself from Nottingham House. Later still, Black spent 15 years in the Athabasca District where he took part in an argument in which 4 Hudson's Bay men were killed.

In the continuing battles between the Hudson's Bay men and the North Westers, Black became more hated than any other North Wester by the men of the Hudson's Bay Company. But in 1820, Black came face to face with George Simpson, who was in charge of a Hudson's Bay post in the Athabasca Country. Black found Simpson a difficult foe.

Simpson went on to become the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the North West Company began to lose the competition. By the time the Companies merged, Sam Black and Peter Skene Ogden had escaped to the territory west of the Rocky Mountains to avoid arrest. Both had been involved in the most scandalous battles between the two companies and, when the companies merged, both were left jobless. Black's letter shows his bitter disappointment:

"The communication received by one from the agents of the late N.W.Co. dated at Fort William, 17th July 1821, upon the subject of the arrangement with the Hudson's Bay Co. you will readily believe was most distressing to my feelings -- That a termination of the various oppositions betweeen the Companies was greatly to be wished for, and sooner or later to be expected, is certainly true; but I never conceived it possible that some of those whose zeal and exertion during the 'conter' brought about probably the necessity of negotiation on the part of our opponents, would be excluded from the benefits hoped for from that termination...." (North West Company correspondence 1800-1827, F.3/2, HBCA).

Ogden and Black fought for their jobs and within a year or two were granted positions in the Hudson's Bay Company. However, Sam Black was sent to take charge of Fort St. John (near Fort St. John, B.C.) and made a difficult exploration of the Finlay River where it ran through the Rocky Mountains -- a wild and absolutely unexplored area at that time -- while Ogden spent years exploring the Snake River District.

Finally after George Simpson believed that Black had been punished enough, he placed him in charge of Fort Colvile on the Columbia River, and later sent him to Fort Nez Perce (Walla Walla, Washington). However, Black was unable to get along with the natives and was transferred to Thompson's River post in 1830, where he spent many years.

Governor Simpson described Black's nature in his "Character Book" of 1832: "....the strangest man I ever knew. So wary & suspicious that it is scarcely possible to get a direct answer from him on any point, and when he does speak or write ... so prolix that it is quite fatiguing to attempt following him. A perfectly honest man and his generosity might be considered indicative of a warmth of heart if he was not known to be a cold blooded fellow who could be guilty of any Cruelty and would be a perfect Tyrant if he had any power....Yet his word when he can be brought to the point may be depended on. A Don Quixote in appearance, Ghastly, raw-boned and lantern-jawed, yet strong, vigorous and active. Has not the talent of conciliating Indians by whom he is disliked, but who are ever in dread of him, and well they may be so, as he is ... so suspicious that offensive and defensive preparation seem to be the study of his Life having Dirks, Knives and Loaded pistols concealed about his Person and in all directions about his Establishment even under his Table cloth at meals and in his Bed."

In 1841, Sam Black died at the hands of a native person at his Thompson's Lake post. In the late autumn of 1840, Black traded for goods with a local native chief, Tranquille, a man who was given this name by the voyageurs for his quiet good nature and calm. Tranquille arrived at the fort to pick up a gun that he had left behind, but Black refused to release the gun and reprimanded Tranquille. Tranquille returned home, chagrined, but relations between the natives and the Hudson's Bay fort remained in good standing.

But over the winter, Tranquille sickened and died. During the funeral speeches, a woman accused Tranquille's nephew of cowardice and urged him to revenge his uncle. The young man blackened his face and travelled to the Thompson's River fort on a freezing cold day, to sit in front of the fire. Black gave him a pipe, food and tobacco and left him alone. But in the late afternoon, as Black was putting his hand on the door of his quarters, the native shot him in the back, killing him immediately.

The native man made his escape, and John Tod came from Fort Alexandria to take over the fort and deal with the murderer. Fort Vancouver men also came north to hunt for the murderer who had abandoned his village and was hidden in the hills near Cache Creek. The Company men closed the fort to the local natives, causing anxiety and suffering among the people now almost entirely dependent on the fort for their supplies.

After a few days search the Hudson's Bay men found the murderer, and with the help of Chief Nicola's tribesmen, captured him. They tied the murderer's hands together and began their journey back to the Thompson's River fort. At the bottom end of Kamloops Lake the murderer upset the canoe they were travelling in, and floated down the river singing his war song. Nicola, who stood with a group of tribesmen on the south bank of the river, ordered his men to kill the murderer, and the boy disappeared under the waters of the Thompson River.

Peter Skene Ogden wrote about his good friend, Black, in Traits of American-Indian Life (London, 1853, reprinted recently in Oregon): "B... was one of my oldest and worthiest friends. Our intimacy had commenced some twenty five years ago, and been ripened by time into the warmest friendship. We had shared in each other's perils; and the narrow escapes we had so frequently experienced, tended to draw still more closely the bond of amity by which we were united. It was our custom to contrive an annual meeting, in order that we might pass a few weeks in each other's company. This renunion naturally possessed charms for both of us; for it was a source of mixed joy, to fight like old soldiers "our battles o'er again," over a choice bottle of Port or Madeira; to lay our plans for the future, and, like veritable gossips, to propose fifty projects, not one of which there was any intention on either part to realize."

Alexander Caulfield Anderson wrote of Sam Black: "Without having had the advantage of a critically correct education he was a man of great mental as well as literary attainments, and to the geology of the country he paid special attention. The geography too of the then only partially explored regions received through him many important additions. Of enormous stature and with a slow and imposing style of address Mr. Black, though he afforded possibly at times some amusement to his colleagues, commanded also their universal respect by his well recognized good qualities." (History of the Northwest Coast, by A.C. Anderson)

When Anderson died in 1884, he had a copy of Sam Black's 1835 map in his possession. This map has many details not shown on any other map of the area, but is very hard to read. It is now stored in the B.C. Archives, map no. CM/B2079, and R.C. (Bob) Harris writes about this map in B.C. Studies, No. 109, Spring 1996.

Saturday, August 29, 2009

A short chronology of the fur trade in the New Caledonia district (northern British Columbia)

One of the things that most interested me as I wrote this book was that the fur trade in the territory we now know as British Columbia had such a short life. New Caledonia's fur trade began with the North West fur trader, Alexander Mackenzie, and his attempt to reach the Pacific Ocean. Alexander Caulfield Anderson's fur trade experience west of the mountains began less than 40 years after that event.

Below I list some of the dates that I feel are important to readers interested in the New Caledonia fur trade -- New Caledonia being the area north of Kamloops, including Fort Alexandria, Fort George, Fraser's Lake, Stuart's Lake, and McLeod's Lake.

In the eyes of the furtraders of the Hudson's Bay Company, New Caledonia was always a part of the Columbia District. Hence, though Alexander Caulfield Anderson spent only a few years in the part of the world we call the Columbia District (modern-day Washington State), he wrote to Governor Simpson in 1849: "I have for some years past had a strong desire to visit home; and it was at one time my intention to apply for leave of absence next year. The unsettled state of affairs, however, has induced me to defer doing so until things are in a fairer train. I have now been so long a resident in the Columbia, that I almost begin to identify myself with its interests ..." (A.C. Anderson to Gov. Simpson, Apr. 17 1849, D.5/25, fo. 122, HBCA).

June 1793: The North West Company was, at this time, looking for a fur trade route to the Pacific Ocean to provide them access to their China trade. In an attempt to find an easy route to the Pacific Ocean, Alexander Mackenzie followed the Fraser River south as far as the place where Fort Alexandria was later built. There the natives advised Mackenzie to follow the West Road River to the Pacific and, following their advice, he successfully reached the Pacific Ocean at modern-day Bella Coola. However, Mackenzie found the route so difficult he did not encourage the North West Company's fur trade to enter the new territory.

1805: Seven years after Mackenzie's exploration, Simon Fraser and John Stuart, also of the North West Company, arrived at McLeod Lake to found the Trout Lake Post -- the first fur trade fort in New Caledonia.

1806: John Stuart, Fraser's second in command, founded Stuart's Lake (later Fort St. James) and the Fraser's Lake post.

1807: Fort George was built at the junction of the Nechako and Fraser River by Simon Fraser and John Stuart; in 1808 it was abandoned, apparently until 1821. (If this was true, than Joseph Rondeau did not spend a winter on the Fraser River at this post.)

1808: Fifteen years after Alexander Mackenzie was advised by the natives in the area of Fort Alexandria to turn back and follow the Blackwater River (Mackenzie's West Road River) to the Pacific Ocean, Simon Fraser and John Stuart ignored those natives' advice and followed the Fraser to its mouth. Fraser's party flew from one hazard to another as they descended the river through its many rapids and canyons. At the mouth of the Fraser they found themselves in danger and quickly escaped upriver. They returned to New Caledonia and did not make any further attempt to find a route to the Pacific Ocean by the Fraser River.

July 1812: John Stuart was ordered to bring the New Caledonia furs to the mouth of the Columbia River. In May 1813 began his journey south, and travelled by the North Thompson River (possibly) and the Okanagan, arrived at Astoria in October.

1814: Fraser's Lake post was founded permanently by the North West Company; it was 21 years old when Alexander Caulfield Anderson took over its charge.

1821: After years of conflict, the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company merged under the name of the Hudson's Bay Company. In the same year, the North West Company men built Fort Alexandria on the east bank of the Fraser River, unaware they were now working for the Hudson's Bay Company.

1824: In the Columbia district, the HBCo's new headquarters was built 100 miles upriver from Astoria (now called Fort George) and called Fort Vancouver.

1824: In New Caledonia, Fort George on the Fraser River was again abandoned.

1826: From this year onward, the New Caledonia brigades brought their furs down to Fort Vancouver by the old brigade trail founded by the men of the North West Company. This trail would be used every year until 1847; it would be only 21 years old when it was abandoned for the new Anderson River trail to Fort Langley.

1827: Fort Langley built on the lower Fraser River.

1827: From the Thompson's River Fort (later Kamloops), Francis Ermatinger explored Seton and Anderson Lake and followed the Lillywit (Lillooet) River, obviously looking for a route to Fort Langley.

1828: Clerk John McDonnell of Fraser's Lake made a cross country journey southward to a river he called the Salmon River, according to Alexander Caulfield Anderson's 1867 map of British Columbia. The only way Anderson could have known of McDonnell's journey is that when he arrived at Fraser's Lake in 1836, he read the old journals of past furtraders -- journals that no longer exist.

1828: Twenty years after Fraser and Stuart descended the Fraser River, HBCo's Governor Simpson and a few of his Chief Traders frightened themselves in their descent of the river. Everyone survived, but Simpson declared that bringing the brigades down by boat would result in certain death nine times out of ten.

1829: Chilcotin Post built on the Chilco River south of Fort Alexandria.

1829: Fort George on the Fraser River was re-occupied.

1835: Alexander Caulfield Anderson entered New Caledonia for the first time, travelling over the old brigade trail to Fort Alexandria. From Fort George he collected the year's leather supplies from Tete Jaune Cache (an adventure he was fortunate to survive), and later took charge of the Fraser's Lake post.

1836: Fort Alexandria was moved from its location on the east bank of the Fraser River, to a position on the west bank. The fort was then 15 years old.

1837: Alexander Caulfield Anderson's soon-to-be wife, Betsy Birnie, travelled with her brother Robert up the brigade trail to Fort Alexandria, to be married. The Okanagan natives gave the brigaders some trouble, and Kamloop's Sam Black galloped south to assist them. Somewhere on his ride southward, the natives ambushed the party and shot Black's horse.

1840: Alexander Caulfield Anderson left New Caledonia by the old brigade trail, travelling all the way to Fort Vancouver. For a few years he was in charge at Fort Nisqually, Puget Sound.

1841: Sam Black was murdered at Kamloops, and Chief Factor John Todd took over. John Todd is credited with exploring and opening up the new brigade trails between Kamloops and Fort Alexandria, about 1843.

Winter 1842: Alexander Caulfield Anderson returned to New Caledonia by the new brigade trail, and took over the charge of Fort Alexandria and the Chilcotin post.

1843: Anderson led the brigade to Kamloops by the new brigade trail, past Green Lake and Loon Lake.

Summer 1843: The all important salmon fisheries up the Fraser River failed, except at the Barriere on the Chilcotin River. Fortunately the vegetable and grain crops at Fort Alexandria were copious and fed everyone, native and white man alike.

May 1844: Fifty-one years after Alexander Mackenzie's journey to the Pacific Ocean, Anderson made a cross-country journey to the isolated cluster of lakes on Mackenzie's West Road River, to choose the place where a new trading post should be constructed. In September the Thleuz-cuz post was finished, and the troublesome Chilcotin post closed down.

Summer 1844: Because of the high water of the Fraser River, the Company's salmon fisheries failed entirely.

Summer 1845: The salmon fisheries on the Fraser River had an excellent year, and the post stored thousands of dried salmon for their winter supply. On one occasion an employee traded for 75 horse-loads of salmon, about 15,000 fish; four days later the same employee again departed the fort, and returned with an additional 11,000 salmon.

January 1846: Fort Alexandria was in process of being moved from the west bank of the Fraser River to the top of the hill on its east bank, possibly because of landslides which had threatened its safety.

1846: 19 years after Francis Ermatinger explored the Lillywit river, Anderson followed his path along the north shore of Seton and Anderson's Lake, and continued down the Lillooet River all the way to Harrison's Lake and Fort Langley, on the Fraser River.

1846: Anderson's return journey took him by the Nicolum River to Snass Creek and over the Coquihalla mountain to Blackeye's camp. The exploration was not considered a success, but Anderson did learn from Blackeye that another trail existed that would lead him to the top of the Coquihalla mountains by an easy route.

1847: 39 years after Simon Fraser made his exploration down the Fraser River, Alexander Caulfield Anderson explored the same river and arrived at Fort Langley in early summer. He considered that it was possible to traverse the canyons of the river both up and down between the native village of Kequeloose and Fort Langley.

1847: Anderson returned to Kamloops on his return journey, travelling up the Fraser River through its canyons and rapids before following native trails that led him over modern-day Lake Mountain to the Nicola Valley. Much work was needed on this trail before it would be a good horse road, but Anderson felt that it would eventually make a good brigade trail.

1848: To the fur traders' surprise, they were forced to use Anderson's 1848 trail before it was ready. No one kept a journal of the outgoing trip, but Anderson said it was harrassing. The incoming brigade had a tougher time, and many modern-day historians have written of this difficult journey up the river that the fur traders now called "Anderson's River." When the gentlemen reached Kamloops, Anderson suggested that his 1846 route over the Coquihalla mountains by Blackeye's trail be used the following year. The idea was accepted, and a clerk was sent to find Blackeyes and have him show him the native trail to Fort Langley.

1849: The New Caledonia brigade travelled out by the Anderson River trail, and in by the new Coquihalla trail. By this time, Anderson was in charge of Fort Colvile and had no further interest in New Caledonia. In fact, when Peter Skene Ogden offered him his Chief Factorship if he took charge of New Caledonia, Anderson refused.

Below I list some of the dates that I feel are important to readers interested in the New Caledonia fur trade -- New Caledonia being the area north of Kamloops, including Fort Alexandria, Fort George, Fraser's Lake, Stuart's Lake, and McLeod's Lake.

In the eyes of the furtraders of the Hudson's Bay Company, New Caledonia was always a part of the Columbia District. Hence, though Alexander Caulfield Anderson spent only a few years in the part of the world we call the Columbia District (modern-day Washington State), he wrote to Governor Simpson in 1849: "I have for some years past had a strong desire to visit home; and it was at one time my intention to apply for leave of absence next year. The unsettled state of affairs, however, has induced me to defer doing so until things are in a fairer train. I have now been so long a resident in the Columbia, that I almost begin to identify myself with its interests ..." (A.C. Anderson to Gov. Simpson, Apr. 17 1849, D.5/25, fo. 122, HBCA).

June 1793: The North West Company was, at this time, looking for a fur trade route to the Pacific Ocean to provide them access to their China trade. In an attempt to find an easy route to the Pacific Ocean, Alexander Mackenzie followed the Fraser River south as far as the place where Fort Alexandria was later built. There the natives advised Mackenzie to follow the West Road River to the Pacific and, following their advice, he successfully reached the Pacific Ocean at modern-day Bella Coola. However, Mackenzie found the route so difficult he did not encourage the North West Company's fur trade to enter the new territory.

1805: Seven years after Mackenzie's exploration, Simon Fraser and John Stuart, also of the North West Company, arrived at McLeod Lake to found the Trout Lake Post -- the first fur trade fort in New Caledonia.

1806: John Stuart, Fraser's second in command, founded Stuart's Lake (later Fort St. James) and the Fraser's Lake post.

1807: Fort George was built at the junction of the Nechako and Fraser River by Simon Fraser and John Stuart; in 1808 it was abandoned, apparently until 1821. (If this was true, than Joseph Rondeau did not spend a winter on the Fraser River at this post.)

1808: Fifteen years after Alexander Mackenzie was advised by the natives in the area of Fort Alexandria to turn back and follow the Blackwater River (Mackenzie's West Road River) to the Pacific Ocean, Simon Fraser and John Stuart ignored those natives' advice and followed the Fraser to its mouth. Fraser's party flew from one hazard to another as they descended the river through its many rapids and canyons. At the mouth of the Fraser they found themselves in danger and quickly escaped upriver. They returned to New Caledonia and did not make any further attempt to find a route to the Pacific Ocean by the Fraser River.

July 1812: John Stuart was ordered to bring the New Caledonia furs to the mouth of the Columbia River. In May 1813 began his journey south, and travelled by the North Thompson River (possibly) and the Okanagan, arrived at Astoria in October.

1814: Fraser's Lake post was founded permanently by the North West Company; it was 21 years old when Alexander Caulfield Anderson took over its charge.

1821: After years of conflict, the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company merged under the name of the Hudson's Bay Company. In the same year, the North West Company men built Fort Alexandria on the east bank of the Fraser River, unaware they were now working for the Hudson's Bay Company.

1824: In the Columbia district, the HBCo's new headquarters was built 100 miles upriver from Astoria (now called Fort George) and called Fort Vancouver.

1824: In New Caledonia, Fort George on the Fraser River was again abandoned.

1826: From this year onward, the New Caledonia brigades brought their furs down to Fort Vancouver by the old brigade trail founded by the men of the North West Company. This trail would be used every year until 1847; it would be only 21 years old when it was abandoned for the new Anderson River trail to Fort Langley.

1827: Fort Langley built on the lower Fraser River.

1827: From the Thompson's River Fort (later Kamloops), Francis Ermatinger explored Seton and Anderson Lake and followed the Lillywit (Lillooet) River, obviously looking for a route to Fort Langley.

1828: Clerk John McDonnell of Fraser's Lake made a cross country journey southward to a river he called the Salmon River, according to Alexander Caulfield Anderson's 1867 map of British Columbia. The only way Anderson could have known of McDonnell's journey is that when he arrived at Fraser's Lake in 1836, he read the old journals of past furtraders -- journals that no longer exist.

1828: Twenty years after Fraser and Stuart descended the Fraser River, HBCo's Governor Simpson and a few of his Chief Traders frightened themselves in their descent of the river. Everyone survived, but Simpson declared that bringing the brigades down by boat would result in certain death nine times out of ten.

1829: Chilcotin Post built on the Chilco River south of Fort Alexandria.

1829: Fort George on the Fraser River was re-occupied.

1835: Alexander Caulfield Anderson entered New Caledonia for the first time, travelling over the old brigade trail to Fort Alexandria. From Fort George he collected the year's leather supplies from Tete Jaune Cache (an adventure he was fortunate to survive), and later took charge of the Fraser's Lake post.

1836: Fort Alexandria was moved from its location on the east bank of the Fraser River, to a position on the west bank. The fort was then 15 years old.

1837: Alexander Caulfield Anderson's soon-to-be wife, Betsy Birnie, travelled with her brother Robert up the brigade trail to Fort Alexandria, to be married. The Okanagan natives gave the brigaders some trouble, and Kamloop's Sam Black galloped south to assist them. Somewhere on his ride southward, the natives ambushed the party and shot Black's horse.

1840: Alexander Caulfield Anderson left New Caledonia by the old brigade trail, travelling all the way to Fort Vancouver. For a few years he was in charge at Fort Nisqually, Puget Sound.

1841: Sam Black was murdered at Kamloops, and Chief Factor John Todd took over. John Todd is credited with exploring and opening up the new brigade trails between Kamloops and Fort Alexandria, about 1843.

Winter 1842: Alexander Caulfield Anderson returned to New Caledonia by the new brigade trail, and took over the charge of Fort Alexandria and the Chilcotin post.

1843: Anderson led the brigade to Kamloops by the new brigade trail, past Green Lake and Loon Lake.

Summer 1843: The all important salmon fisheries up the Fraser River failed, except at the Barriere on the Chilcotin River. Fortunately the vegetable and grain crops at Fort Alexandria were copious and fed everyone, native and white man alike.

May 1844: Fifty-one years after Alexander Mackenzie's journey to the Pacific Ocean, Anderson made a cross-country journey to the isolated cluster of lakes on Mackenzie's West Road River, to choose the place where a new trading post should be constructed. In September the Thleuz-cuz post was finished, and the troublesome Chilcotin post closed down.

Summer 1844: Because of the high water of the Fraser River, the Company's salmon fisheries failed entirely.

Summer 1845: The salmon fisheries on the Fraser River had an excellent year, and the post stored thousands of dried salmon for their winter supply. On one occasion an employee traded for 75 horse-loads of salmon, about 15,000 fish; four days later the same employee again departed the fort, and returned with an additional 11,000 salmon.

January 1846: Fort Alexandria was in process of being moved from the west bank of the Fraser River to the top of the hill on its east bank, possibly because of landslides which had threatened its safety.

1846: 19 years after Francis Ermatinger explored the Lillywit river, Anderson followed his path along the north shore of Seton and Anderson's Lake, and continued down the Lillooet River all the way to Harrison's Lake and Fort Langley, on the Fraser River.

1846: Anderson's return journey took him by the Nicolum River to Snass Creek and over the Coquihalla mountain to Blackeye's camp. The exploration was not considered a success, but Anderson did learn from Blackeye that another trail existed that would lead him to the top of the Coquihalla mountains by an easy route.

1847: 39 years after Simon Fraser made his exploration down the Fraser River, Alexander Caulfield Anderson explored the same river and arrived at Fort Langley in early summer. He considered that it was possible to traverse the canyons of the river both up and down between the native village of Kequeloose and Fort Langley.

1847: Anderson returned to Kamloops on his return journey, travelling up the Fraser River through its canyons and rapids before following native trails that led him over modern-day Lake Mountain to the Nicola Valley. Much work was needed on this trail before it would be a good horse road, but Anderson felt that it would eventually make a good brigade trail.

1848: To the fur traders' surprise, they were forced to use Anderson's 1848 trail before it was ready. No one kept a journal of the outgoing trip, but Anderson said it was harrassing. The incoming brigade had a tougher time, and many modern-day historians have written of this difficult journey up the river that the fur traders now called "Anderson's River." When the gentlemen reached Kamloops, Anderson suggested that his 1846 route over the Coquihalla mountains by Blackeye's trail be used the following year. The idea was accepted, and a clerk was sent to find Blackeyes and have him show him the native trail to Fort Langley.

1849: The New Caledonia brigade travelled out by the Anderson River trail, and in by the new Coquihalla trail. By this time, Anderson was in charge of Fort Colvile and had no further interest in New Caledonia. In fact, when Peter Skene Ogden offered him his Chief Factorship if he took charge of New Caledonia, Anderson refused.

Sunday, August 23, 2009

New Brigade Trail, Copper Creek to Loon Lake

From Kamloops, the brigaders heading toward Fort Alexandria rode along the north shore of Kamloops Lake until they reached Copper Creek.

Somewhere, in one of those folds of the hills across the lake, is the creek named Copper Creek for a vein of copper the natives discovered.

Where Copper Creek swung eastward, another river flowed in (Carabine Creek), and the brigaders followed to the third lake, where they set up camp.

Anderson's map indicates that the camp was known as Camp a la Carabine.

He also noted that as the brigaders left the shores of Kamloops Lake to ride up Copper Creek, they passed through the northern edge of rattlesnake territory.

According to Alexander Caulfield Anderson's map of the brigade trails, Criss Creek was known as Riviere a l'eau Claire.

When I ventured to Criss Creek, I thought that the brigades followed Criss Creek down its busy streambed to the Deadman River.

They did not.

They did not.

The brigaders crossed Criss Creek well above the place where it flowed into the Deadman River, and climbed over a second height of land.

The trail finally crossed the Deadman River well to the north of Criss Creek, at a place where they had to build switchbacks down the hillside to reach the river.

These switchbacks are clearly marked on Alexander Caulfield Anderson's 1867 Map, which as of June 2009, is available to researchers.

For years, this map was hidden away in a darkened room in the depths of the archives storage, and almost no one saw it.

When I asked to see the map earlier this summer, the archivist talked for half an hour on the importance of this map for British Columbians.

The archives staff scanned a copy of it in 2008, but because it was still sealed in its mylar (plastic) envelope the copy came out unfocused and with a blue-ish cast.

Because of requests (mine and others), the archives staff carefully removed the map from its mylar envelope and scanned a permanent copy into their computer system.

Everyone can now own a copy of this map, but it will cost you.

To our right, Criss Creek.

To our right, Criss Creek.Below is a photograph of Deadman River, looking toward Kamloops Lake to the south.

This photograph was taken well south of Criss Creek, and I don't have any photographs of the portion of the river that the brigade would have crossed.

However, I think the river would look much the same as in this photograph -- except that it was less open and its banks were bordered by bigger hills.

Deadman River, to our left.

The photograph below shows the bottom of Loon Lake, and includes a view of the hill that the brigade circled around (see map above).

Coming in from Kamloops, the brigaders would have ridden into Loon Lake from the left side of the photograph, and as they left they would have ridden slightly left of the photographer.

In his unpublished manuscript, British Columbia, (Mss. 559, PABC) Anderson described the country the brigade trail passed through with these words: "Beautiful prairies, bordered by lofty hills sparsely scattered with timber, stretch around. ... Groves of the Aspen appear here and there. The Balsam Poplar shows itself at intervals only, along the streams. The white racemes of the Service-berry flower, and the chaste flowers (blossoms) of the Mock Orange, load the air with their fragrance. Every copse re-echoes with the low drumming of the Ruffed Grouse; the trees resound with the muffled booming of the Cock of the Woods. The "Pheasant" whirrs past; the scrannel-pipe of the larger Crane -- an ever watchful sentinel -- grates harshly on the ear; and the shrill whistle of the Curlew as it soars aloft aides the general concert of the re-opined year. I speak still of Spring; for the impressions of that jocum season are ever the most vivid, and naturally recur with the greatest force in after years."

When my sister and I visited Loon Lake, we were delighted by the many little creatures that popped out of the cattle guards to whistle at us.

They are a marmot, apparently, but not the yellow-bellied marmot. There are 40 or more breeds of marmot in the province, and I would be delighted if someone were able to identify these comical creatures for me.

They are a marmot, apparently, but not the yellow-bellied marmot. There are 40 or more breeds of marmot in the province, and I would be delighted if someone were able to identify these comical creatures for me.

The bottom photo is of the end of Loon Lake, where the brigades would have set up camp for the night. Imagine the gentlemen riding in and dismounting from their horses; the provisioning brigade lighting the fires and putting the food on to cook.

The hard-working horses would be set loose to roll in the grass, before being hobbled for the night.

As evening falls, the men sit around the fires, smoking and talking. Then they roll themselves up in their blankets and sleep on the ground.

They would begin work early the next day -- at about 4 o'clock in the morning.

Maps, Fort Langley via Kamloops to Fort Alexandria

I know that my readers have some difficulty in figuring out where our trail is leading us, and to make it easier I am putting in maps to show both where we have been, and where we will be going.

I know that my readers have some difficulty in figuring out where our trail is leading us, and to make it easier I am putting in maps to show both where we have been, and where we will be going.The first map begins at Fort Langley, on the Fraser River, and follows the Fraser both east and then north to the Thompson River and beyond.

As you have begun to understand, this part of British Columbia is almost entirely mountains or highlands. Only the Fraser River valley most of the way to Hope, and the Nicola Valley, are flat, open grasslands. This will change as we move north toward Fort Alexandria.

The above photograph was taken at the replica Fort Langley, but a building of this sort would appear in any fur trade fort in the territory.

Map 1 -- Fort Langley to Kamloops, by the Fraser, Thompson, and Nicola Rivers. The dotted line indicates the journey we have taken.

The second map, below, is showing you where we will go, as we follow the new brigade trail north to Fort Alexandria, and the old brigade trail east from Fort Alexandria to modern-day Little Fort, the North Thompson River and, finally, Kamloops.

The second map, below, is showing you where we will go, as we follow the new brigade trail north to Fort Alexandria, and the old brigade trail east from Fort Alexandria to modern-day Little Fort, the North Thompson River and, finally, Kamloops.

This is a big country, and I think you will understand how large when you see the scale I have included in both maps. I hope you continue to enjoy our travels around British Columbia, following Alexander Caulfield Anderson's trails.

Sunday, August 16, 2009

Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia, Part 9

From Nicola Lake, the furtraders reached the Thompson's River (or Kamloops) fort by crossing the highlands between the Nicola valley and the Kamloops Lake valley.

From Nicola Lake, the furtraders reached the Thompson's River (or Kamloops) fort by crossing the highlands between the Nicola valley and the Kamloops Lake valley. It's beautiful country -- grass-covered hills with numerous small lakes nestled amongst them.

The photograph at the top of the page shows Stump Lake.

The second photograph is of Rock Lake, and the hill behind is called Brigade Hill.

The third photograph was taken at the top of the highlands, and shows the bare country the trails led through.

It was an easy journey from Nicola Lake to the Kamloops post, and in Anderson's various journals he hardly mentions the country.

It was an easy journey from Nicola Lake to the Kamloops post, and in Anderson's various journals he hardly mentions the country.

For him and other furtraders, the highlands were always the easiest part of the journey and, homebound at least, meant they were approaching the comfort of the Kamloops fort.

In 1847 Anderson left Kamloops at 10 o'clock and camped that night at the west end of Nicola Lake. On his return journey the men left the west end of Nicola Lake (probably about 4 am.) and arrived at Kamloops at 2 pm.

The only time Anderson ever mentioned this country was on his return from his 1846 exploration, when he wrote: "Leave San Poila River and strike across through a beautiful country to Kamloops, where we arrived at 6 1/2 pm." (Return trip, Journal of an Expedition..., A/B/40/An3.1, PABC)

The photograph above is an older photograph showing Kamloops Lake as viewed from the highlands the fur traders rode over to reach Kamloops.

The old Thompson's River fort -- and the newer Kamloops fort which replaced it in 1843 -- stood at the forks of the North Thompson and South Thompson Rivers, at the right-hand edge of this photograph (or maybe even outside the photo).

The second photograph is a more modern photograph and shows Kamloops Lake from its south shoreline. The Kamloops fort stood on the banks of the rivers that flowed into the lake at its east end -- about where the plume of smoke in this photograph rises.

Below is a map of Kamloops Lake, with Thompson's River post on the east side of the North Thompson River (before 1843) and the Kamloops fort on the west side. Chief Trader Sam Black had been in charge of the Thompson's River post for many years, but when he was murdered, Chief Factor John Tod took over the posting.

Though Sam Black was the man who explored and recorded many of the native trails in the area, John Tod was the man most responsible for the placement of the new brigade trail between the new Kamloops fort and Fort Alexandria to the north.

The photographs below are of Kamloops Lake from its south bank, and they scan from the west end of the lake (near modern-day Savona) to the east.

You will note that on the above map I have indicated Copper Creek, Deadman River, and Criss Creek. After 1843 the brigade trail between Kamloops -- now in its new position on the west bank of the river -- and Fort Alexandria led along the north bank of Kamloops Lake to Copper Creek.

The horses of the brigade followed Copper Creek north to Carabine Creek, and crossed a ridge or two to Criss Creek.

They then crossed Criss Creek and trotted over another height of land to enter the valley of the Deadman River by a series of switchbacks down a steep hill.

The new brigade trail between Kamloops and Fort Alexandria was first travelled by the brigade in 1843.

Before that time the incoming and outgoing brigades had travelled across the Thompson Plateau to the North Thompson River, then south on its east bank to the Thompson's River post on the east side of the river.

The relocation of the Thompson River post to the west bank of the river coincided with the opening of the new brigade trail from Fort Alexandria, and was a more convenient location for everyone involved in the fur trade.

This is a view of the west end of Kamloops Lake taken from its south shore.

The furtraders "Thompson's River" flows out of the lake's west end through a series of almost impassible canyons.

North and west of the lake is Deadman's River and the brigade trail to Fort Alexandria, after 1843.

This photograph is slightly to the east of above photo, and we are looking across Kamloops Lake toward Copper Creek, on its north shore.

The canyons of the Thompson River were, for many years, the only barrier between building a brigade trail between Kamloops and Fort Alexandria that avoided the Thompson Plateau.

Once the easy access up Copper and Carabine Creeks was discovered, there was little to prevent the furtraders from using this route as their new brigade trail.

Picture 150 loaded packhorses and their outriders following the trail from Kamloops along the north shore of this lake, and disappearing into the fold in the hills that is Copper Creek.

The normal New Caledonia brigades consisted of many strings of horses, with each string of seven or nine horses in the care of two men.

At the head of the brigade rode the gentleman-in-charge, and immediately behind him came the employee assigned the duty of keeping up the communications between the gentleman and the various brigades that followed.

Behind the gentleman and the horses that carried his luggage trotted the horses of the provisioning brigade.

On arrival at camp at night, the two men of this brigade unloaded their goods and lit the fires that cooked the men's suppers.

Then they erected the leather tents that the gentlemen slept in, and made their beds.

Each horse carried two 90-lb packs, or 180 lbs. of trade goods.

Loading the packhorses began at 4 o'clock in the morning, and it would take five hours to make all the horses ready.

Loading the packhorses began at 4 o'clock in the morning, and it would take five hours to make all the horses ready.

The brigade travelled about 15 miles a day, and the pack day, or hitching, ended before dusk so that the men could set up camp in daylight.

Travelling in a brigade was dusty and noisy, with the songs or curses of the employees, and the bells of the horses.

Travelling in a brigade was dusty and noisy, with the songs or curses of the employees, and the bells of the horses.

Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia, Part 8

In summer of 1847, Alexander Caulfield Anderson and five of his Fort Alexandria men left Kamloops on horseback, crossing the hills south of the fort into the Nicola Valley. Anderson hoped that they would find a new brigade trail to Fort Langley, on the lower Fraser River.

In summer of 1847, Alexander Caulfield Anderson and five of his Fort Alexandria men left Kamloops on horseback, crossing the hills south of the fort into the Nicola Valley. Anderson hoped that they would find a new brigade trail to Fort Langley, on the lower Fraser River.

On May 21, the explorers followed the well-used native trail to the usual ford that crossed the Nicola River west of the lake, but found the river too high to cross.

Anderson had intended to follow the native trail across the valley to the place where the Nicoamen River flowed into the Thompson, but because of the flooded river, he was forced to follow its north bank all the way to its junction with the Thompson.

In above map, Nicola River to the left of the map leads northward to the shores of the Thompson River. In 1847, Anderson rode south from Kamloops by Stump Lake and Stump Creek to Nicola Lake, then along the north shore of the lake to the place where the Nicola River flowed west out of the lake.

In above map, Nicola River to the left of the map leads northward to the shores of the Thompson River. In 1847, Anderson rode south from Kamloops by Stump Lake and Stump Creek to Nicola Lake, then along the north shore of the lake to the place where the Nicola River flowed west out of the lake. By the mid-1840's it seemed as if most of the fur trade trails to the south of Kamloops passed through the Nicola Valley.

Alexander Caulfield Anderson passed through this valley in two of his four explorations, and both the Coldwater River valley and the Quilchena-Otter Creek routes formed part of the later brigade trails.

Not only that, but at some point the portion of the Okanagan brigade trail through Monte Lake and Creek was abandoned for a new trail that led through Douglas Lake into the Nicola Valley.

In the shot to the right we are looking at Stump Lake, on the height of land north of the Nicola Valley on the furtraders' route to Kamloops.

In the shot to the right we are looking at Stump Lake, on the height of land north of the Nicola Valley on the furtraders' route to Kamloops. In 1847, Anderson rode past this lake to reach Nicola Lake.

The shot below shows the hills to the north of the Nicola Valley and lake, where Stump Lake Creek flowed into Nicola Lake.

From the east end of the Nicola Valley, the Nicola River flowed in from Douglas Lake. At this point the river is much larger than the smaller Nicola River flowing out of the west end of the lake. Sometime before 1843, the fur traders abandoned the part of the brigade trail through the Okanagan and, instead of travelling through Monte Lake, took a trail that led them from the shores of Okanagan Lake up the "Riviere de Jacques," following the height of land north of Nicola River and Douglas Lake (probably passing through Jack's Lake) to reach Kamloops by Stump Lake.

The large photograph above shows the Nicola Valley, looking west along the valley and lake from its east end.

The smaller photograph is of the Nicola River where it flows into the east end of Nicola Lake from Douglas Lake.

To the south of Nicola Lake is Quilchena and Quilchena Creek.

The furtraders of the time called Quilchena Creek "Riviere Bourdignon."

The furtraders of the time called Quilchena Creek "Riviere Bourdignon."

Native trails that followed Quilchena Creek through the range of hills pictured above, led into the area the fur traders called the Similkameen.

The Similkameen was the area around Red Earth Forks (modern day Princeton) and Otter Lake, where the native chief Blackeye had his camp.

The Similkameen was the area around Red Earth Forks (modern day Princeton) and Otter Lake, where the native chief Blackeye had his camp. In 1846, Alexander Caulfield Anderson explored the Nicolum River (see posting, June 25, 2009) as far as modern-day Rhododendron Flats (see posting, July 25, 2009), and climbed the mountain range to the north. From the top of the Coquihalla range Anderson followed the Tulameen River canyon south to the Similkameen, where he ran into Blackeye and his son-in-law.

Blackeye told Anderson of an easier route up the mountains and, a year later, the son-in-law showed the furtraders one of many native routes over the mountains.

In 1849 the incoming New Caledonia brigade used this trail for the first time, and passed over it so successfully that, for years, it served as the main route between Kamloops and Fort Langley. The above shots show the country that the fur traders rode through coming north from Blackeye's camp, following Otter Creek and Quilchena River toward Nicola Lake. (This area will be covered more fully in a later posting.)

Southwest of Nicola Lake is the Coldwater River Valley. Anderson's 1847 exploration from Fort Langley brought him up the Anderson and Utzlius Rivers to the Coldwater River and, eventually, to Kamloops.

Southwest of Nicola Lake is the Coldwater River Valley. Anderson's 1847 exploration from Fort Langley brought him up the Anderson and Utzlius Rivers to the Coldwater River and, eventually, to Kamloops. Anderson thought that, with a little work, this trail would make a good brigade trail.

In 1848, the outgoing New Caledonia and Fort Colvile brigades were forced to use this trail before it was fully prepared for horses, and they had a disasterous journey to and from Fort Langley. On August 22 they arrived at Kamloops, with no one in a good mood. Thirty five horses (or more) had been lost or killed, and 14 bales of goods had gone missing. The gentlemen had a meeting, and Donald Manson condemned the route as impassible, while Anderson agreed that it appeared more rugged by horseback than it had been when he travelled it by foot the year before. At last, Anderson saw there could be no agreement, and suggested that the brigades use Blackeye's Trail over the mountains to the Coquihalla River -- the trail he had partially explored in 1846.

The photograph above shows the Coldwater River valley from the mountains to the south.

The photograph below is shot from the same place, and looks toward the Nicola Valley (and modern-day Merritt) from the Coquihalla heights.

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson around British Columbia, Part 7

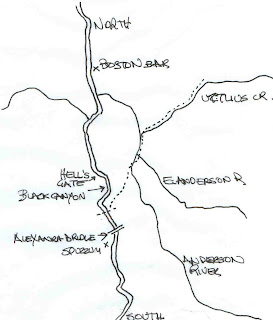

The map to our left shows the Thompson River between the Nicola River and the Fraser. To the north-east is Kamloops Lake; and the Kamloops post stood at the east end of that lake. The Black Canyon which blocked the river between Kamloops Lake and the mouth of the Nicola made travel down that part of the Thompson River extremely difficult (if not impossible), and all the native and furtraders' trails in this area were designed to avoid that section of the Thompson River.

On the morning of May 19, 1847, Alexander Caulfield Anderson set out on his third journey across or around the mountains that lay between Kamloops and Fort Langley. From Kamloops, Anderson and five employees rode their horses over the hills south of Kamloops, to the Nicola Valley.

From Nicola Lake, Anderson and his men planned to ford the Nicola River and take a native trail that led across the valley directly to the mouth of the Nicoamen River. This trail would bypass the rough banks of the Thompson River south of its junction with the Nicola.

But the high waters of the Nicola River prevented their crossing at the normal ford, and forced them along a path that followed the Nicola's north bank to the Thompson River. From the Little Forks, Anderson and his men walked the banks of the Thompson River west toward its junction with the Fraser.

The photograph at the top of the page is of the Thompson River looking to the east toward the Kamloops Fort, and it is taken from the west of the Nicoamen River. This second photograph shows the Thompson River as we look toward the Fraser, taken at about the same place. In this second photograph, the river bank the furtraders walked was the south bank, closest to the photographer.

The photographs below show where the Nicoamen River flows into the Thompson down a straight cliff into a meadow. Obviously the fur-traders' path passed across the Nicola Valley to follow a valley east of the falls and joined the Nicoamen where it flowed into the Thompson River, just behind the photographer. To the east of the falls there is a fold in the hills which indicates the path the furtraders might have followed to reach the mouth of the Nicoamen River.

At any rate, this was the trail not taken. The explorers camped a few miles from the junction of the Nicola with the Thompson, and began again early the next morning. By 7.30 the next morning the explorers had reached the junction of the Thompson and Nicola River, and Anderson sent his horses back to Kamloops with their guides. The explorers crossed the Nicola River in canoes borrowed from the natives who lived nearby.

At any rate, this was the trail not taken. The explorers camped a few miles from the junction of the Nicola with the Thompson, and began again early the next morning. By 7.30 the next morning the explorers had reached the junction of the Thompson and Nicola River, and Anderson sent his horses back to Kamloops with their guides. The explorers crossed the Nicola River in canoes borrowed from the natives who lived nearby. From this point, Anderson led his men on foot along the rocky shores of the river's south bank. The Thompson foamed with white-topped rapids as it flowed swiftly past them, and the air grew hot and sultry.

Though their path led up and down the hills of the uneven river bank, Anderson thought it suitable for horses. At the end of that sultry hot day, the tired men of the exploring party camped on a hill close to the banks of the Nicoamen River.

They started off before four o'clock the next morning, and crossed the mouth of the Nicoamen on a fallen tree. The day was hot, and they walked past many rapids before stopping to enjoy the first meal of the day, close to the place where the Thompson River forced its way through a narrow channel into the Fraser.

Here Pahallak, the native chief who had acted as Anderson's guide the previous year, joined the party. With Pahallak travelled a large group of natives who Anderson described as a "scampish looking set of vagabonds." As usual, when Hudson's Bay men met a group of natives, everyone shook hands until their wrists were sore.

Here Pahallak, the native chief who had acted as Anderson's guide the previous year, joined the party. With Pahallak travelled a large group of natives who Anderson described as a "scampish looking set of vagabonds." As usual, when Hudson's Bay men met a group of natives, everyone shook hands until their wrists were sore.

The remaining photograph is of the Thompson River between Nicoamen and the river's junction with the Nicola River, where modern-day Spences Bridge now stands. North and east of Spence's Bridge the Thompson River was confined in a narrow and rapid-filled canyon that no one chose to travel.

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Seton

Alexander Seton was born at Tottenham, Middlesex, on October 4, 1918, and was the eldest surviving son of Alexander Caulfield Anderson's uncle, Alexander Seton. In November 1832 (the same month his cousin Alexander arrived at Fort Vancouver), Alexander Seton purchased a commission as Second-Lieutenant in the Royal North British Fusiliers, and served in Tasmania and India with his regiment.

In 1847 Seton made Captain and was transferred to the 74th Highlanders, stationed in England and Ireland. In 1852, as Lieutenant-Colonel, Alexander Seton took command of the drafts of raw recruits destined for the Cape of Good Hope, where his own regiment was already involved in the Kaffir War. Seton was 38-years-old when the paddle-wheeled iron troopship, Birkenhead, sailed from Ireland on January 7 1852.

At two o'clock in the morning of February 26, the Birkenhead struck a rock in False Bay, 20 miles southeast of Cape Town, and foundered. In spite of the urgency of the situation, Seton issued his orders with perfect calm -- "Women and Children First!" The crew prepared the ship's boats and loaded the man soldiers' families into them, while the soldiers themselves stood at attention on the Birkenhead's sloping decks.

The soldiers knew they were doomed, that there were not enough boats to carry them ashore and the distance was too far to swim. Seton made his way to the stern of the ship where he admitted to another officer that he could not swim. One of Seton's two horses made it to shore, but he did not. A survivor reported that Seton had been killed by the fall of a mast.

In 1847 Seton made Captain and was transferred to the 74th Highlanders, stationed in England and Ireland. In 1852, as Lieutenant-Colonel, Alexander Seton took command of the drafts of raw recruits destined for the Cape of Good Hope, where his own regiment was already involved in the Kaffir War. Seton was 38-years-old when the paddle-wheeled iron troopship, Birkenhead, sailed from Ireland on January 7 1852.

At two o'clock in the morning of February 26, the Birkenhead struck a rock in False Bay, 20 miles southeast of Cape Town, and foundered. In spite of the urgency of the situation, Seton issued his orders with perfect calm -- "Women and Children First!" The crew prepared the ship's boats and loaded the man soldiers' families into them, while the soldiers themselves stood at attention on the Birkenhead's sloping decks.

The soldiers knew they were doomed, that there were not enough boats to carry them ashore and the distance was too far to swim. Seton made his way to the stern of the ship where he admitted to another officer that he could not swim. One of Seton's two horses made it to shore, but he did not. A survivor reported that Seton had been killed by the fall of a mast.

Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson Around British Columbia, Part 6

The outgoing New Caledonia brigade left Fort Alexandria on May 2 1846, and this year, Alexander Caulfield Anderson travelled south with them. From Kamloops, Anderson planned to explore for a new brigade trail that would connect Kamloops and Fort Langley.

The outgoing New Caledonia brigade left Fort Alexandria on May 2 1846, and this year, Alexander Caulfield Anderson travelled south with them. From Kamloops, Anderson planned to explore for a new brigade trail that would connect Kamloops and Fort Langley.Anderson was confident he could find a good horse road between the two posts. On May 15, he led his men along the south shore of Kamloops Lake and crossed the Thompson River to follow it west. The explorers crossed both the Deadman and Bonaparte Rivers, and followed Hat Creek west through Marble Canyon. So far, this was familiar territory. The trail that Anderson and his men followed was the route by which the Fraser River salmon were delivered to Kamloops every summer.

Anderson and his men arrived on the banks of the Fraser River and set up camp near the native fishing village where the Kamloops employees traded for salmon.

Below the fishing village, the Fraser River flowed into a steep-sided and broken river trench, and in the distance loomed Fountain Ridge. The proposed track passed down this rugged river bank and over Fountain Ridge, but Anderson saw it was impossible to take horses through this broken land.

The first photograph is of the Fraser River below Fountain Ridge, and shows the river trench that the Fraser River flowed through at this point. To the left is a photograph of the mouth of Bridge River, where it flows into the silted Fraser River south of Fountain Ridge.

On the morning of May 20, the exploring party crossed the Fraser River in canoes borrowed from the natives, and followed the west bank of the river as it curved around the end of Fountain Ridge. They crossed the mouth of the Bridge River by the native bridge that existed there for many years. After a ten-mile hike down the Fraser's rough banks, they arrived at the mouth of the river the natives called Pap-shil-qua-ka-meen. This rapid-filled river (Seton River) tumbled downhill from two isolated bodies of water that wound between high mountain peaks.

On the morning of May 20, the exploring party crossed the Fraser River in canoes borrowed from the natives, and followed the west bank of the river as it curved around the end of Fountain Ridge. They crossed the mouth of the Bridge River by the native bridge that existed there for many years. After a ten-mile hike down the Fraser's rough banks, they arrived at the mouth of the river the natives called Pap-shil-qua-ka-meen. This rapid-filled river (Seton River) tumbled downhill from two isolated bodies of water that wound between high mountain peaks. The party broke for a meal at the head of the first lake a short distance upriver, and looked at the narrow stretch of water that lay before them. The twelve-mile long Seton Lake curved between precipitously sloping mountains that reached a thousand feet into the air, and Anderson saw that the tops of the ridges were white with snow.

The photograph above shows both Anderson Lake (to the right) and Seton Lake (to the left), from the top of the ridge that separates the two lakes from the Bridge River valley. To get to this point from modern-day Lillooet, cross the Fraser River and travel west toward Carpenter Lake, following the signs to Shalalth. The road will take you over a ridge of land and down the mountain's south slopes to the shores of the lakes -- with many switchbacks and spectacular views.

But the road we take to get to Anderson and Seton Lakes today did not exist in Anderson's day. From the east end of Seton Lake, Anderson's party walked the lake's north shore to the strip of land that separated the two lakes. The photograph to the left is of Seton Lake, and its north shore is to the left side of the photograph.

But the road we take to get to Anderson and Seton Lakes today did not exist in Anderson's day. From the east end of Seton Lake, Anderson's party walked the lake's north shore to the strip of land that separated the two lakes. The photograph to the left is of Seton Lake, and its north shore is to the left side of the photograph. Anderson had already suspected that this route could never make a good brigade trail, but he now knew this trail could never be traversed by the two hundred horses of the typical brigade.

Still, the men were halfway to Fort Langley and they had no alternate route. They camped that night at the place where the lake jogged westward, close to a sizeable native village.

Still, the men were halfway to Fort Langley and they had no alternate route. They camped that night at the place where the lake jogged westward, close to a sizeable native village.

Still, the men were halfway to Fort Langley and they had no alternate route. They camped that night at the place where the lake jogged westward, close to a sizeable native village.

Still, the men were halfway to Fort Langley and they had no alternate route. They camped that night at the place where the lake jogged westward, close to a sizeable native village. Anderson wrote in his journal:

"A ripe strawberry was picked here this evening. But the background is the most rugged and dreary-looking tract I ever met with; nor had I any previous conception that so mountainous a region could exist so near the banks of a large stream like Fraser's River."

At the end of Seton Lake, Anderson crossed over a wooded point of land to another lake, and walked a few more miles up the shoreline of Anderson Lake before stopping for breakfast on a low point of land. The steep, bare mountains that ringed the first lake had faded behind them, and rounded tree-covered hills had taken their place.

The photograph above is of Seton Portage -- once called Birkenhead Portage. Years after he first visited this place, Alexander Caulfield Anderson named Seton Lake and Birkenhead Portage for his cousin and childhood playmate, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Seton of the 74th Highlanders -- who, in 1852, drowned in the troopship Birkenhead off South Africa.

In the final photograph, we are looking west down the length of Anderson Lake toward the Lillooet River (nowhere near the town of Lillooet) and Fort Langley. I visited this place in 1993. As I came up the many switchbacks above the lakes, a golden-biege bear tumbled down the hill and landed on the road directly in front of my car -- a foot in front of the hood. The bear glanced at me with dark-rimmed cleopatra eyes and kept on running. Just as he disapeared down the slope, a truck's hood edged around the corner in front of me, with two men leaning forward to find the bear they had frightened.

I visited this place in 1993. As I came up the many switchbacks above the lakes, a golden-biege bear tumbled down the hill and landed on the road directly in front of my car -- a foot in front of the hood. The bear glanced at me with dark-rimmed cleopatra eyes and kept on running. Just as he disapeared down the slope, a truck's hood edged around the corner in front of me, with two men leaning forward to find the bear they had frightened.

I visited this place in 1993. As I came up the many switchbacks above the lakes, a golden-biege bear tumbled down the hill and landed on the road directly in front of my car -- a foot in front of the hood. The bear glanced at me with dark-rimmed cleopatra eyes and kept on running. Just as he disapeared down the slope, a truck's hood edged around the corner in front of me, with two men leaning forward to find the bear they had frightened.

I visited this place in 1993. As I came up the many switchbacks above the lakes, a golden-biege bear tumbled down the hill and landed on the road directly in front of my car -- a foot in front of the hood. The bear glanced at me with dark-rimmed cleopatra eyes and kept on running. Just as he disapeared down the slope, a truck's hood edged around the corner in front of me, with two men leaning forward to find the bear they had frightened.Following Alexander Caulfield Anderson Around British Columbia, Part 5

In 1847, James Douglas and Peter Skene Ogden asked Alexander Caulfield Anderson to make his third exploration between Kamloops and Fort Langley -- this time by the Fraser River. On May 19, Anderson left Kamloops and travelled on foot through the Nicola Valley and down the south bank of the Thompson River. Where the Nicoamen River flowed into the Thompson from the south, Anderson met his native guide, Pahallak, who led him west toward the Fraser River.

In 1847, James Douglas and Peter Skene Ogden asked Alexander Caulfield Anderson to make his third exploration between Kamloops and Fort Langley -- this time by the Fraser River. On May 19, Anderson left Kamloops and travelled on foot through the Nicola Valley and down the south bank of the Thompson River. Where the Nicoamen River flowed into the Thompson from the south, Anderson met his native guide, Pahallak, who led him west toward the Fraser River.From the Thompson's River junction with the Fraser, the party walked south along the east bank of the Fraser River, passing by a number of native villages as they made their way. When the explorers set up camp that evening on the rocky shores of the Fraser River, all were exhausted by their long hike over the hot, dry hills. Anderson estimated they had covered 28 miles of rough ground, and it was 90 degrees in the shade.

At every village, the fur traders' presence was announced by the high-pitched barks and howls of the woolly-coated and bushy-tailed dogs that lived in the villages up and down the Fraser River and all through the Thompson River district. These were the Salish wool dogs, and these dogs were shorn like sheep and their wool used to weave the fine blankets for which these native tribes were celebrated. Simon Fraser had reported seeing these animals years earlier, and Alexander Mackenzie mentioned them. Now it was Anderson's turn to comment on these historic and now extinct dogs that appeared to him as ghostly and mysterious animals that gamboled around the villages, some shorn while others sweltered under a crop of flowing fleece that shone white in the sunshine. It was only when the explorers approached the villages that they could identify these animals as dogs.